By Date

Alice Tang named to 30 Under 30

All life copies DNA unambiguously into proteins. Archaea may be the exception.

Learn about research from the lab of Assistant Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Dipti Nayak.

Learn about research from the lab of Assistant Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Dipti Nayak.

Excerpt from UC Berkeley News: "A study finds that one microbe, a member of the Archaea, tolerates a little flexibility in interpreting the genetic code, contradicting a 60-year-old doctrine." Read the full Berkeley News article here.

UC Berkeley dean’s research inspires emerging treatment for rare bone disease

Learn about research from the lab of Dean of Biological Sciences, Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Richard Harland.

Learn about research from the lab of Dean of Biological Sciences, Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Richard Harland.

The Fall 2025 Transcript newsletter is here!

Learn about MCB's exciting research, new faculty, molecular medicine lab, department-wide retreat, alumni and more!

Learn about MCB's exciting research, new faculty, molecular medicine lab, department-wide retreat, alumni and more!

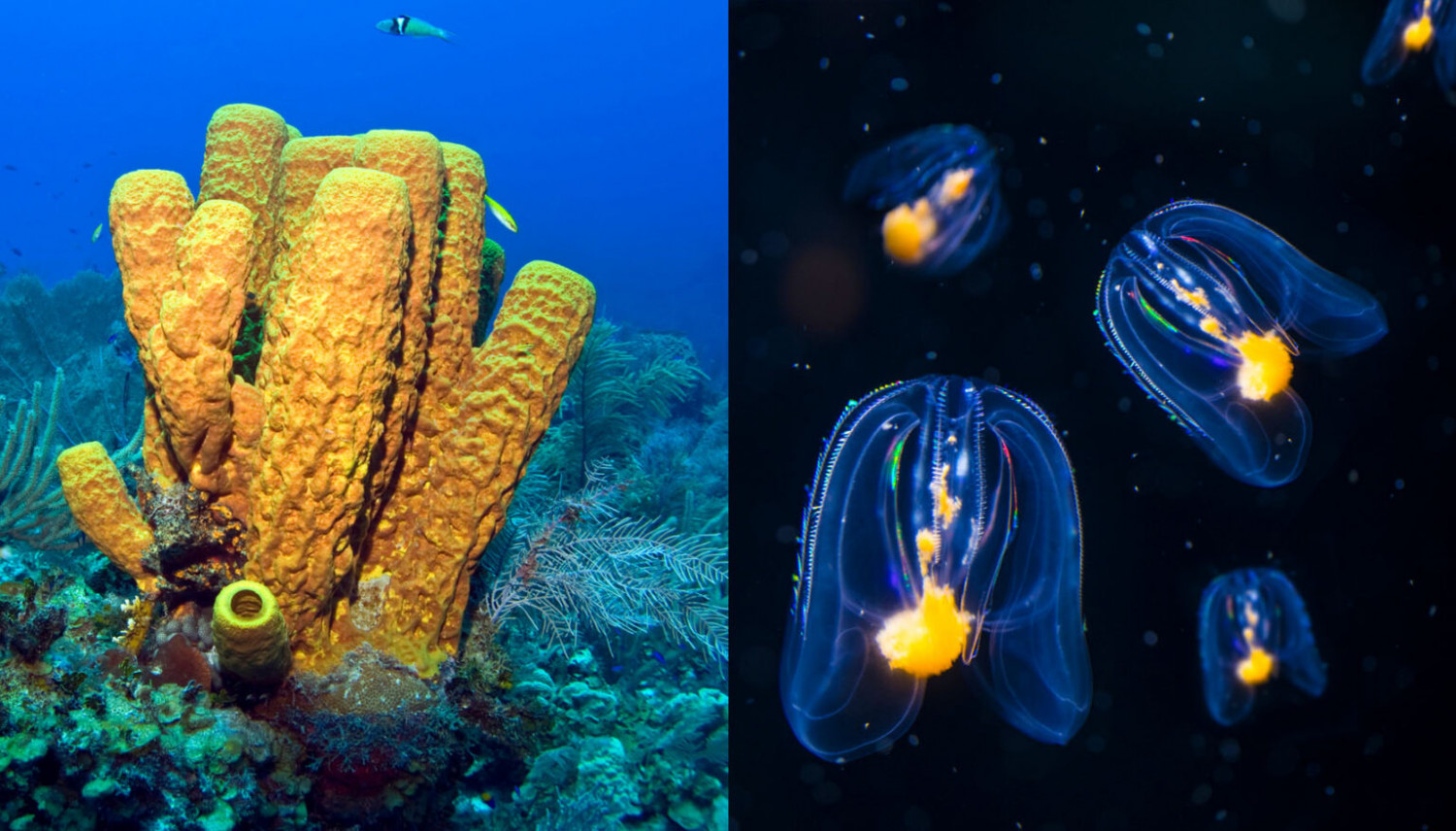

Did the first animal look like a sponge or a comb jelly? The debate continues.

Learn about new research from the lab of Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Nicole King.

Learn about new research from the lab of Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development Nicole King.

Nature provides the answers

Researchers pioneer greener way to extract rare earth elements

Four BioE Faculty Named 2025 Highly Cited Researchers

Even moderate heat waves depress sea urchin reproduction aling the Pacific coast

Biologists believed that urchin reproduction along the Pacific Coast would only be affected by marine heat waves at lethal ocean temperatures, a new study conducted by IB Assistant Professor Daniel Okamoto and other marine biologists at UC Berkeley suggests that this threshold of susceptibility, for urchins and other marine species, may be at lower temperatures than previously thought. Read the full article here.

Origin of Life - Nov 18

The origins of ever-evolving life are never sufficiently explained; innovations in the complex origins of life are continually being expanded into new horizons. Join Wonderfest’s guest speaker, Distinguished IB Professor and Director of the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Dr. Charles Marshall, on November 18, 2025, as he explores the integral role of energy and information in the past, present, and future of life on Earth. Read the full article here.

In Memoriam: Michael J. Chamberlin

Michael Chamberlin

Michael Chamberlin

Miller awarded Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Supplemental Grant

Associate Professor of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Structural Biology Evan Miller was selected as one of 16 Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Supplemental Grant recipients for 2025. This award, from the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, provides funds to support Miller's research project "A Generalizable Method to Improve the Brightness of Long-Wavelength Fluorophores". Read more about the award and 2025 recipients here.

Associate Professor of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Structural Biology Evan Miller was selected as one of 16 Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Supplemental Grant recipients for 2025. This award, from the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, provides funds to support Miller's research project "A Generalizable Method to Improve the Brightness of Long-Wavelength Fluorophores". Read more about the award and 2025 recipients here.